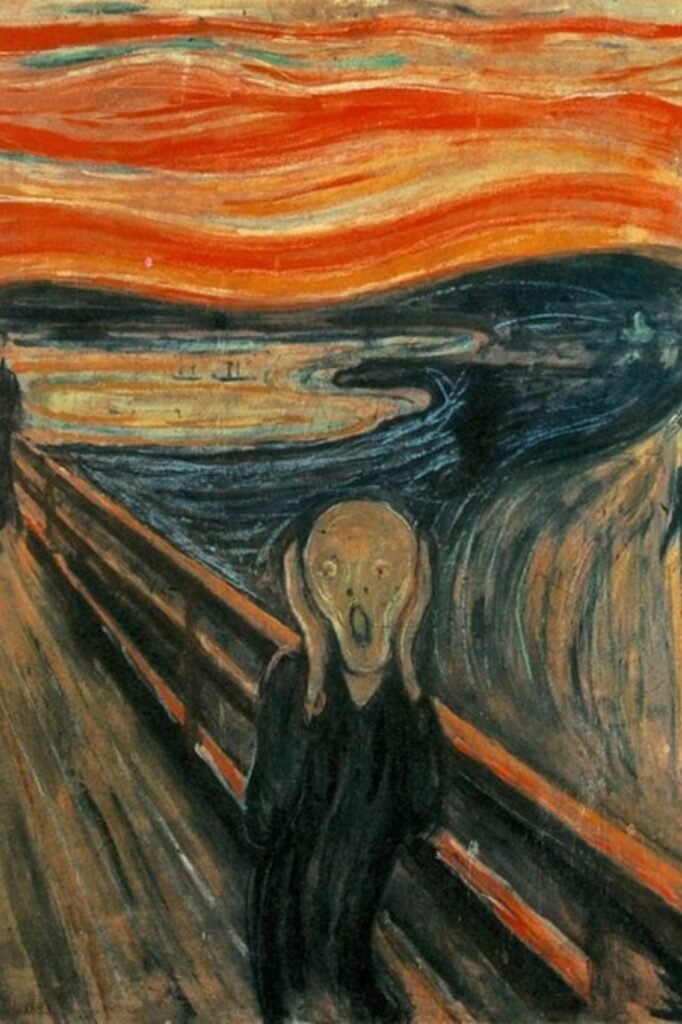

A Mummy’s Curse and a Silent Scream: The Hidden Layers of Edvard Munch’s Life and Masterpiece

The Scream

Chahapoya Peru Mummy

The Unlikely Muse

A Scream He Wouldn’t Hear

The Scream On Display At The National Gallery, Oslo, Norway

Silencing the Storm: The Scream That Stays Out

, carved across versions from 1893 to 1910 on rough cardboard—Munch’s refusal to soften his pain. On January 22, 1892, near Oslo Fjord, he wrote: “I felt as though a vast endless scream passed through nature.” Not his scream—nature’s. He’s not letting it out; he’s keeping it from piercing his ears, a subtle twist that redefines the myth.

Death’s Relentless Toll: The Family That Fuelled Munch’s Madness

EDVARD MUNCH 1933

CHRISTIAN MUNCH (FATHER)

LAURA CATHERINE (MOTHER)

JOHANNE SOPHIE (SISTER)

Munch’s life was a relentless funeral march. Born in 1863 in Christiania (now Oslo), he was one of five children, but death claimed them one by one. His mother, Laura Cathrine, died of tuberculosis in 1868 when Munch was just five, her lungs ravaged by the disease that left her coughing blood. His older sister, Johanne Sophie, followed in 1877 at 15, her body wasted by the same illness—her deathbed agony later haunting his canvas The Sick Child. His father, Christian, a doctor and religious zealot, crumbled into depression, dying in 1889 of a heart condition worsened by grief and despair. He’d told young Edvard their losses were “divine punishment for our sins,” a cruel sermon that branded Munch’s psyche with guilt and dread.

His younger sister, Laura, slid into schizophrenia by her teens, her mind fracturing into delusions—committed to an asylum by 1892, her screams became Munch’s ghosts. His only brother, Peter Andreas, a budding doctor, died in 1895 at 31, felled by pneumonia that drowned his lungs in fluid. Munch himself, frail and sickly, survived childhood fevers that kept him bedridden, sketching to escape a house of mourning. By 1908, his own sanity buckled—a nervous breakdown landed him in a clinic, his lifelong fear of madness no longer a shadow but a reality.

Madness Marketed as Genius

Chaos in Creation

The Silent Genius: Why The Scream Endures

The Scream lasts because it’s Munch’s madness and silence made universal. Five family members lost—two to tuberculosis, one to pneumonia, one to madness, one to despair—his pain is ours. That mummy-like figure lets us pour in our dread. It’s not a scream let out—it’s one he wouldn’t hear, a twist that echoes forever.

is Munch’s soul bared—a jagged cry from a life gutted by loss, sold with shrewd brilliance. Next time you face it, see the Peruvian ghost, feel the blocked wail, and hear the quiet of a man who turned a family’s doom into eternity.