Pablo Picasso stands as one of the most influential artists of the 20th century.

Born in Spain in 1881, Picasso was an artistic virtuoso from a young age, pioneering ground breaking styles like Cubism and collage.

By 1937, when Picasso created his famous anti-war painting Guernica, he was the most renowned artist in the world.

Guernica was born out of Picasso’s reaction to the tragic bombing of the eponymous Basque town by Nazi warplanes during the Spanish Civil War.

Although Picasso tended to avoid politics in his work, he was moved by the brutality of this attack to depict the universal anguish and destruction of war.

He completed the massive 11 x 25 ft painting in just 35 days using a monochromatic palette of black, white and grey.

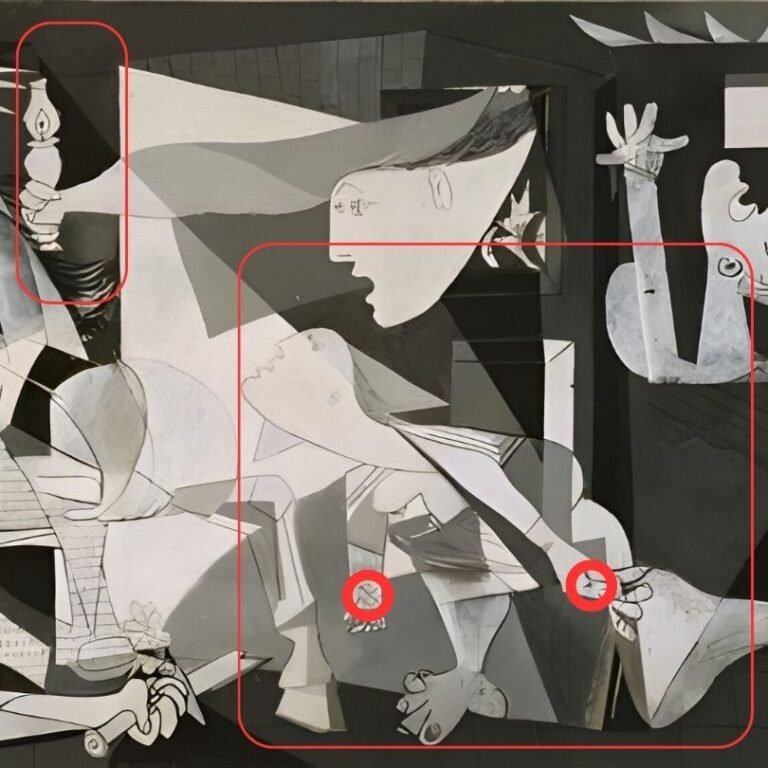

Picasso incorporates stylistic elements from his Cubist and surrealist periods into Guernica’s disjointed, overlapping composition. The painting is filled with symbolic figures and objects that reflect death, violence, suffering and hope. A mother cradles her dead child, a horse screams in agony, a soldier lies in defeat, a burning woman calls out for help, an electric bulb glares overhead. Despite its modernist elements, the classical grouping of figures and triangle of light give visual structure.

Guernica became an iconic anti-war work, its message resonating through the World War II and Vietnam eras up to today. Eight decades later, the wrenching imagery continues to stir emotions and provide perspective on the human toll of all military conflict. Picasso’s Guernica remains one of history’s most unforgettable artistic statements against the brutality of war.

Here is a detailed description and analysis of the key elements and figures in Picasso’s Guernica:

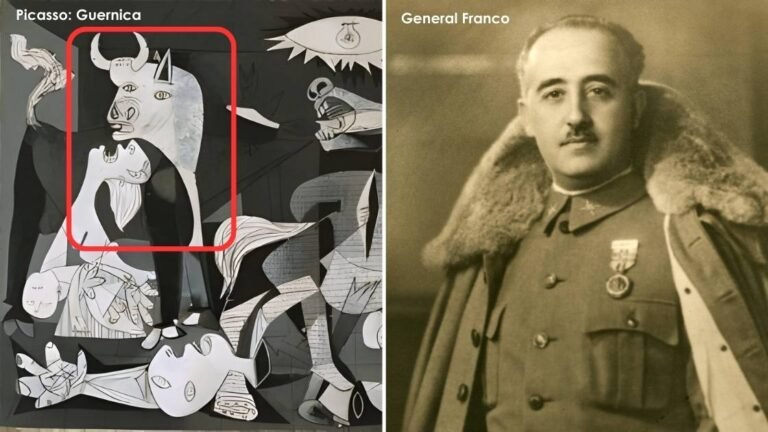

The Bull:

In this painting, the bull is the only part of the painting that directly looks at the viewer. The bull was one of Picasso’s favourite themes because of its association with Spanish Bull Fighting. In Guernica, the bull takes on a more sinister meaning. The only figure facing the viewer head-on, its cold, unfeeling eyes seem to implicate us in the horrors before it. The bull’s massive form stands impassively over the suffering figures, embodying the sheer brutality and ruthless oppression of fascism and the Franco regime or General Franco himself. Through this potent figure, Picasso connects the violence of the bull ring – the traditional national pastime – with the living nightmare of fascism’s assault on the Spanish people.

The Weeping Woman and Fallen Soldier:

Beneath the hulking bull, a mother clutches her lifeless child, cradled in her bare and exposed breasts that once gave him life. She throws back her head, mouth open in a wail of anguish, eyes streaming in pictographic tears. This pieta evokes the Virgin Mary mourning Christ, as war defiles maternal love and innocence.

Further down lies the broken corpse of a soldier, his disjointed body strewn across the ground. One severed arm lifts a shattered sword, now a futile symbol of defeat and failure. Yet hope sprouts from it – a white poppy, an emblem of remembrance. The soldier’s other hand bears stigmata, linking him to holy sacrifices.

In death, he transcends the futility of war through allegories of peace and salvation amidst his ruin. Even as bombs fall, Picasso offers glimmers of optimism, a message that humanity might rise again.

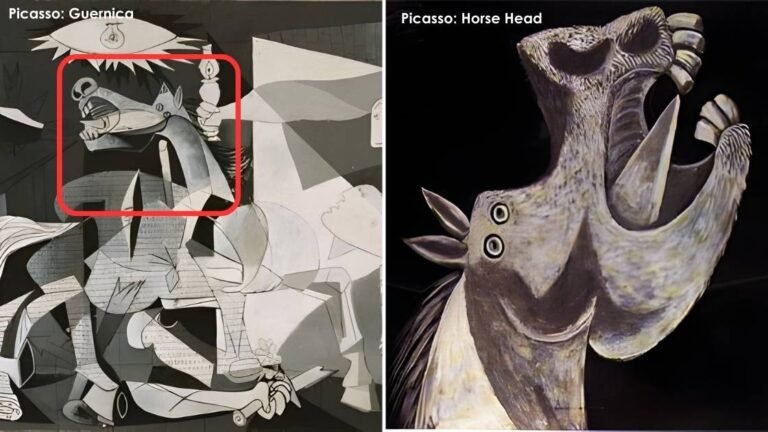

The Horse:

A screaming horse appears in the center, collapsing from a gaping wound but struggling to stay upright. It represents the people of Guernica and its painful cries echo their suffering. Its strained posture may reference horses in Picasso’s early works as well as paintings of battle horses throughout art history.

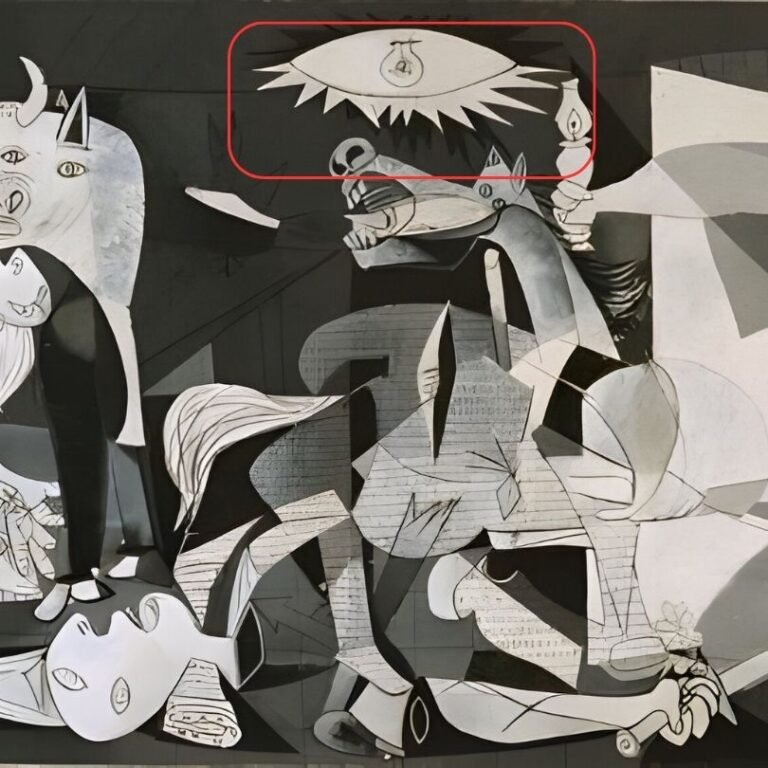

The Light Bulb:

A sole electric bulb glares down upon the scene, the only explicit vestige of 20th century technology in Guernica’s primitive tableau of suffering. The bulb’s meaning remains ambiguous, much like the painting itself. Perhaps it symbolizes the harsh, revealing light of God observing humanity’s descent into madness below. More literally, the lightbulb may signify the advanced bombers and explosive technology that razed Guernica itself. In Spanish, “bombilla” means lightbulb, evoking “bomba” – bomb. With this sly dual meaning, Picasso links lighting and bombing as twin emblems of modernity’s capacity to illuminate, but also to destroy. The bomb-bulb’s harsh glow exposes war’s brutality, its technological might indivisible from the white heat of burning flesh and the blackness of death.

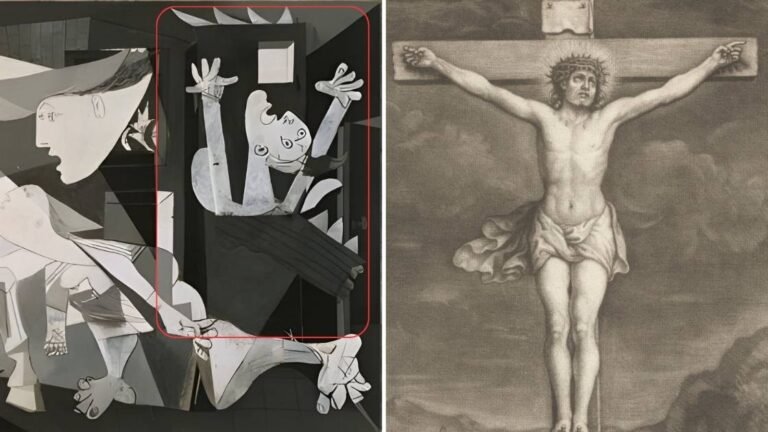

The Burning Woman:

The burning woman is perhaps the most iconic part of this painting. The woman is trapped in a burning building, arms outstretched in a pleading gesture, perhaps to God. The flames and crumbling walls surround her as death closes in, reflecting the civilian victims of Guernica. Her pose is reminiscent of Christian crucifixions and martyrdoms.

The Oil Lamp and the injured woman:

In contrast to the electric lightbulb, a small oil lamp sits on the floor, its tiny flame illuminating the scene. The lamp represents hope and the resilience of the Spanish people. Its light suggests moral clarity in the darkness and chaos of war. Looking up at the light another woman writhes in agony, clutching her leg as blood gushes from her knee. She also has the mark of the stigmata. Desperately she tries to stanch the flow, hand soaked crimson. Her face turns beseechingly toward a small oil lamp resting on the ground. Unlike the stark electric bulb, this humble light bathes the entire scene, its fragile flame a lone beacon of hope.

The lamp embodies the spirit of the Spanish people, illumination amidst darkness, resilience even as the bombs fall and bodies break. While the electric bulb is cold and impersonal, the lamp’s warm glow nurtures the possibility of renewal.

Yet its meaning, like the painting itself, remains open to interpretation. For just as Guernica resists any singular reading, so does this little lamp offer multiple meanings – solace and redemption, or merely the illusion of hope amidst hopelessness.

Conclusion:

Eight decades after its creation, Guernica retains its power as one of the world’s most impactful anti-war statements. Picasso channeled his outrage over the bombing of innocent civilians into a timeless screed against the senseless brutality of all military conflict. Through wrenching imagery of death, anguish, and destruction, he reminds us of war’s horrific toll.

Yet amidst the chaos, Guernica offers glimmers of optimism – a candle flame, a flower, a woman gazing upward as if appealing to higher powers for salvation. Even at our darkest moments, Picasso suggests, hope endures. The figures themselves, although battered, lift their voices in a collective cry for peace.

Guernica stands as Picasso’s masterpiece, a painting that transcends specific historical events to protest universal human suffering. The artist created an icon that has been embraced, debated, and revered by generations. As long as mankind wages war upon itself, Picasso’s monumental mural will continue to remind us that from devastation can emerge not just anguish, but also hope, resilience, and moral purpose.

Bonus: 10 Facts about Guernica:

- Guernica kept memories of the bombing alive while also resonating as a universal cry against war’s brutality. When a Nazi officer saw the mural and asked Picasso if he did it, Picasso asserted “No, you did” – linking the painting to Fascist atrocities.

- Guernica was a commissioned piece for the 1937 Paris Expo, but Picasso abandoned his original idea after learning of the attack. The bombing gripped him unlike previous passive projects.

- The painting suggests torn newspaper, perhaps as Picasso learned of the bombing through print reports. Newsprint shapes the horse’s chainmail armor.

- Though Picasso lived in Paris, Spanish patriotism and injustice inspired Guernica. He never returned to his homeland, yet the attack’s civilian deaths shook him.

- In 1974 antiwar activist Tony Shafrazi vandalized the painting with spray paint while on display in New York. Cleaned immediately, Shafrazi was charged with criminal mischief.

- Picasso mandated that Guernica stay in New York until Spain reestablished democracy. Only in 1981 did Spanish negotiators finally repatriate the mural.

- A photographer documented the painting’s progress, likely inspiring Picasso’s stark black-and-white palette versus initial color.

- Picasso deliberately ordered matte house paint to reinforce the mural’s grim tone and monochrome mood.

- Hidden images emerge throughout – a skull over the horse, a bull in its bent leg, dagger tongues in howling mouths.

- Two signature Picasso motifs appear – the Minotaur dominates left, while a harlequin sheds a diamond tear, symbols of power and duality.

I like what you guys are usually up too. This kind

of clever work and reporting! Keep up the wonderful works guys I’ve added you guys

to my own blogroll.